- Home

- Denis Avey

The Man Who Broke Into Auschwitz Page 3

The Man Who Broke Into Auschwitz Read online

Page 3

The Italians built a chain of elaborate fortified positions starting on the coast and sweeping south-west deep into the desert. Their camps had romantic, aromatic names – Tummar, Rabia and Sofafi – as if they lay on some desert spice trail. Now there were 250,000 on the Italian side and we arrived to join Allied forces which were vastly outnumbered in the air and on the ground, just 100,000 of us in total.

Cairo was our last interlude before the war became real, the last chance to relax before the true toughening-up began, the process that was to prepare me well for captivity and all that followed. Three of us, Charles Calistan, Cecil Plumber and I, set off to discover the dubious delights of the city with a couple of older soldiers who knew their way around. Cecil was a thoughtful bloke, with a high forehead and a keen eye. I knew him as a brilliant wicketkeeper from my local cricket team, back in Essex. Now those breezy days on the village green were a distant memory. Instead of the thrushes and larks, black kites sailed across a city as exotic as it was mysterious, heaving with allied soldiers: New Zealanders, Indians and Australians as well as the British.

A horse-drawn gharrie overtook us crammed with lads dressed in khaki, all in high spirits and heading off for a wild night. I was pained to see the distress of the beast trapped between the shafts. They clambered out in front of us, shouted, ‘Three cheers for the gharrie driver’, then bolted without paying.

There were camels bearing improbable loads, donkeys being beaten with sticks by riders whose feet scraped the ground and all around us were street urchins calling for ‘Baksheesh, baksheesh.’ Small boys hawked trinkets of dubious value. Others pressed us to buy suspicious-looking fruit juices and second-rate figs. A dusty tram rattled by at speed, with sparks flying from its wheels. There was a yellow haze in the air, a mixture of fumes and airborne sand particles, all set off with the smell of open sewers.

Stepping off a noisy street, where the horse-drawn vehicles battled for space with trucks, we ducked into the Melody Club. They called it the Sweet Melody. Somebody had a sense of humour. The entrance was veiled by two musty blackout curtains, though outside there were blue streetlamps and lights shining from windows and doorways everywhere. Brushing through the first of them, I tripped on something sack-like on the floor. In the gloom, I picked out the body of an Australian soldier comatose at my feet.

We pushed through the second curtain into the dim light and smoke of a dingy bar. A band was playing on a tiny stage behind a barrier of barbed wire. They needed it. They were struggling to be heard in the raucous atmosphere. The place was crammed, with lads on leave from the desert looking for some kind of release. There were bullet holes in the ceiling and heaven knows what else on the floor. The Australians were usually blamed for it. They were first-class men out on the desert but back in Cairo, drunk, they could be the worst.

There was a destructive excitement in the air. It was no place to relax. We had just got our drinks when there was shouting from a corner table. The lad in the middle of the rumpus picked up a chair and threw it backwards over his head to crash into another table of revellers. One of his own mates then knocked him out cold with a right hook. He might have been finishing the original scrap or maybe pre-empting a major brawl. It calmed things down and the unconscious chair-thrower was carried outside to join the chap blocking the doorway. The rest of them straightened the chairs and their uniforms and the buzz returned to its earlier, rowdy level.

Officers would automatically head for the bars of the famous Shepheard’s Hotel where Cairo’s high society congregated. Mere soldiers like us had to be well turned out to get in. The cool of the terrace bar was a different world. A suited man played an upright piano; wickerwork armchairs were arranged around the tiled floors; Egyptian waiters wearing long white galabeyas served drinks on shiny trays they balanced on one hand. This was more like it. I was a corporal then and a far better leader than a follower. I was determined to get a field commission and Shepheard’s looked more like the life for me.

Later in the cool bustle of the evening, we crossed the English Bridge over the Nile, guarded by four enormous bronze lions. ‘See those?’ shouted one of the lads. ‘Every time a virgin crosses the bridge they roar, so watch it.’ There was uncomfortable laughter. With the desert approaching, there was endless talk about girls. Gnawing away at us was the knowledge that we would be facing bullets soon enough. Not surprisingly, sex came up quite often. It turned out that most of us were still virgins and prepared to admit it. I was twenty-one and sex before marriage wasn’t on back then. People wouldn’t believe it now. Many of the lads were in the same boat. We were old enough to die and yet sexually we were still innocents. I was super-fit and of course exhausted at the end of a day of training so maybe I didn’t think of it. For some it became an obsession.

One street name was often on soldiers’ lips. The Berka was the centre of Cairo’s oldest profession. It was out of bounds to all ranks, ringed by large, white signs and black crosses and often raided by the military police. That didn’t stop the lads but the whole thing offended me somehow. I could understand that young men going into action might want to go there first, but it appalled me and I never followed them. Now, on the eve of heading off into the desert, I knew deep inside I was starting to close down. Distraction could mean the bullet and I was determined to survive whatever they would throw at me. That meant staying focused.

‘Pick up your parrots and monkeys, you’re off.’

The order sounded comical but we knew what it meant. We were leaving for the desert. They called it going ‘on the blue’ because it was an exotic, dry sea, a place of wonder to a boy from a green, rainy country. We were joining the 7th Armoured Division, resilient and nomadic, the Desert Rats.

The slow train trundled through stations with improbably playful names like Zagazig. Then it was west along dazzling white sand dunes bordered by a sharp, blue sea, past a stagingpost with a name that meant nothing to us then, El Alamein, and a station named Fuka, which attracted much more comment.

We arrived at Mersa Matruh where the British had dug in, creating a fortress, and were living a troglodyte existence in anticipation of a further Italian advance. We were there to upset the Italians so we headed deeper into the desert. The rutted track south soon widened as convoys of trucks jinked around the trickier patches.

My fantasy of undulating sand dunes sculpted by the wind was replaced by a stony reality: arid and inhospitable with occasional scrub and patches of dull coloured sift-sand. They called it ‘porridge country’ and this was to be the scene for our struggle.

A tremendous escarpment of great strategic importance dominated the landscape. The 600-foot high Haggag el-Aqaba runs parallel to the sea and eastwards towards Sollum, where its rocky cliffs jut out over the Mediterranean with the hairpin bends of the Halfaya Pass. The British had already seen action there as the Italians advanced. We rechristened it Hellfire Pass.

The battalion was testing Italian positions with night patrols. I was in ‘B’ Company and at the end of October we began cutting telegraph wires and mining roads to stop Italian reinforcements coming to assist the remote desert fortresses.

I was learning to understand the desert better, feeling the immensity of Africa with its 180 degrees of sky and roasting daytime temperatures that could plunge to near freezing as you lay out below the star-spangled night. There was no escaping the desert dust storms when they arrived. The billowing wall of sand of a khamsin would climb high into the air like a moving mountain and sweep across to hide the sun, stripping loose paint from vehicles like a blast of heated iron-filings. The driving grains of sand stung you right through your clothes. During the dust storms you just had to take cover. The only water was to be found in the ‘birs’, ancient wells and cisterns, some Roman, whose contents were brackish at best and on one occasion contained a floating dead donkey. That quenched our thirst, though not for long.

As night fell we would leaguer up, parking the vehicles, mainly trucks and Bren gun carriers, in a huge

defensive square. Guards would be posted on the outside and changed every two hours whilst the rest of us would try to sleep as cooler evenings gave way to chilly nights. There were no campfires in the darkness, just greatcoats, if you had them, for warmth.

I would get to know the Bren gun carrier pretty well over the months to come. It was a nippy, tracked armoured vehicle, completely open, with a powerful Ford V-8 engine in the middle. There was space for one and sometimes two Bren gunners in the back and it had a Boys anti-tank rifle fired by the commander from the front seat right next to the driver.

I got to know the oily underside of the beast as well because at night I would dig a depression in the sand, then run the carrier over it and wriggle down between the heavy tracks for some protection from shrapnel, bombs or bullets. I would spread out my bedroll, which was little more than a thick blanket rolled into a plastic sheet, check my .38 revolver was handy and the grenades were in reach, then get my head down.

We would be woken by the guard well before first light, so a crack on the head from an oily sump offered the usual start to the day. The camp spluttered slowly into life as engines started, not always the first time. We would break up the leaguer, still cold and sleepy, and deploy out into the desert, at least a hundred yards apart, to await a dawn attack. No one wanted to give low-flying Italian Savoia bombers an easy target. Then the chilly wait began as we scanned the horizon. Only when the sky brightened and the contours of the desert gradually emerged could we relax and think about breakfast.

I’d set about making the first brew of the day as if life depended upon it. I’d be cold and hungry and I needed it straight away so I’d do it the desert way. I’d cut an old petrol can in half, fill it with sand, pour high-octane fuel into it and balance the billy-can of water on top. Then, standing well back, I’d throw a match at the lot. ‘Whaff!’, a cloud of black smoke would rise into the air. The spectacular blast would offer the first warmth of the day and brought the billy to the boil in no time.

We had welcomed the cooler weather at first but it was beginning to get much colder at night now and that wasn’t a lot of fun. Then we started to get rain overnight as well, as if our spirits needed further dampening. Ours was still mostly a phoney war then and we were plunged back into more training: PT, map reading, arms drill and the skills of night patrolling. All of which were about to come in handy.

Chapter 3

We went into action. One night we were sent to blow-up an Italian fuel dump, twelve of us under Platoon Sergeant-Major Endean, with three explosive experts to do the damage. The desert belonged to us at night as the Italians didn’t move around much. Good navigation made all the difference, knowing how far back to stop the trucks so they wouldn’t hear us, but not so far that we couldn’t get there on foot in the time available. Before kick-off, we lined up face to face to do a basic visibility check. Anything light on the uniform might be spotted and bring the bullets raining on us. Next, working in twos, we shook each other down. Jangling keys or the rattle of coins could give the game away and sound travelled at night.

With the final weapons checks completed it was evening before the three trucks set off across the rocky landscape. We de-trucked ten miles from the target and, guided by Endean and his trusty compass, we trekked the last section on foot in silence. We were whacked when we arrived but surprise was everything.

As the outline of the dump became visible Endean gave the signal and we crawled forward to take up positions in the gravel. More hand signals and we were fanning out into a semicircle. It was safer that way. The last thing we wanted to do was to knock out our own chaps if a shooting match began.

I lay prostrate in the darkness with the Lee-Enfield trained on the dump. I tried to get comfortable. It might be a long wait.

To my right I saw the outline of the explosives lads going in heads down and crouching low as they went, shadows instantly lost in the darkness. The minutes passed. Silence was always good. More waiting. Suddenly there they were, all three of them, heads down and running like the clappers. We took aim at the camp and waited for the shooting to begin. The first two blasts seemed small and sent rocket-like flashes into the night sky. There was an unnatural pause, probably only seconds, before an enormous explosion and a ball of fire turned the night orange. I pressed deeper into the sand, as the faces around me were suddenly illuminated.

That was when you expected it to come to the boil. The Italians would usually begin firing wildly into the night. This time it was a doddle and we slipped back into the desert. If anyone survived they never bothered to chase us.

We gathered at a rendezvous point a safe distance away, checked everyone was OK and began the long slog back to the trucks. Before the first signs of dawn, we were back safe and hoping to sleep.

When I look back, I can identify the experiences that changed me and prepared me mentally for the deprivation of Auschwitz. Life in the desert often meant being cold and hungry with nothing better to look forward to than bully-beef, and hard tack – dog biscuits to anyone else. Then there was Maconochie’s meat stew. They’d had that in the First World War trenches too. Very occasionally, we might shoot a gazelle and we would have a feast that we could make last for days. Some of the lads would try and fire at them from moving vehicles but the desert just wasn’t flat enough. Bouncing over the mounds we called camel humps ruined their aim. As a farm boy I knew the best way to do it was on foot so I went stalking.

Sometimes we could barter with the Bedouin but that was rare and fraught with misunderstanding. They waved to greet you with the palms of their hands facing backwards, waggling their fingers as if to beckon you over. When you obliged they would be confused, wondering what it was you wanted. The misunderstanding was worth it if the prize was an egg or two but fruit and vegetables, which was what we really needed, were unheard of. Sometimes we would capture Italian food supplies, tinned tunny fish or rice, but usually just tomato purée. They seemed to eat little else.

Our diet was dreadful and we were all woefully undernourished so we got used to illness. A scratch would soon turn into a suppurating wound that would refuse to heal and could lead to blood poisoning. These desert sores plagued us throughout the campaign. Medics were rare and the only treatment they offered was to lift the scab and hope for the best. I still have the scars along my forearms seventy years later.

Hygiene was poor, as you can imagine with all the flies. We were regularly struck down with ‘gyppie-tummy’, and diarrhoea in the desert is no fun. Doing the necessary was tricky enough anyway. You would dig a hole and crouch down. Within seconds, flying dung beetles would begin thumping into your backside. They were more accurate than the average Stuka but whereas the Stukas released their bombs and left, these creatures would fly straight into your swaying rear. It was their preferred landing method. They would then flop down into the sand and start rolling up the meagre content of your bowels before retreating backwards with it, God knows where.

When we were in one spot for longer we would carve a desert toilet seat by cutting a hole in the top of one of the wooden cases that the fuel cans came in. They were about three feet tall and you could sit like a king as you surveyed the shifting sands.

Water was handed out at the rate of a gallon per man but we had to top up radiators and do everything with that so there wasn’t much to drink. The water came in flimsy metal containers coated with wax, which invariably cracked as the tins had been tossed around. It tasted either of rust or candles. Washing was a luxury we couldn’t afford in combat. When the pressure was off we would wash our hands and face as best we could, then use a shaving brush to apply minimal amounts of water to the rest of the body. It usually ran out before the job was done.

All too often we were dependent on the bowser man. I never knew his name. To everyone he was just the bowser man, plain and simple. He roamed the desert with a captured Italian tanker truck almost at will, touring the birs in search of water. He could be gone for days, always alone. He was a small, mysterious

man who could read the desert and converse comfortably in Arabic with the Bedouin. Being on the blue had got to him. If he returned and caught you sitting on one of our improvised fuel-case toilets he would go wild, pull out his .38 revolver and drive the bowser round and round, shooting at the box between your legs. Nobody knew why. Despite the indignity of having a wooden lavatory shot from underneath you, he never hurt anyone and, mad though he was, everyone just accepted him.

Then came the biggest show so far. General Wavell decided on a surprise attack on the Italian desert fortresses. The details were kept very quiet of course. Everything was on a ‘need to know’ basis and the lads didn’t need to know. That’s how it was. Our part was to go out and chart the Italian minefields and the other defences round their camps so that the tanks leading the assault could charge straight in through the gaps.

On 7 December, vast columns of men and machinery moved into position under cover of darkness as the desert winter began to bite, leaving soldiers shivering and nervous ahead of the battle. Two days later, in the very early morning, tanks, guns and infantry were led to the start line for the attack. The route for the vehicles marked with hurricane lamps which were shielded from the enemy by petrol cans, cut open and tilted over. The soldiers were near enough to smell coffee and the other aromas of breakfast wafting from the Italian camps. At 0700 hours our guns let rip with a massive barrage and then the attack on their positions began. The Italian tanks were useless with very thin armour. We knocked out twenty-three of theirs in the first fifteen minutes then captured thirty-five more and took 2,000 prisoners for the loss of fifty-six men. In the grim arithmetic of war, that was a good start.

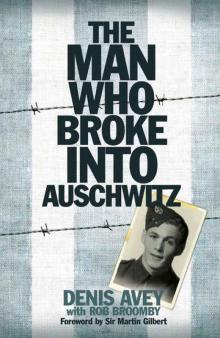

The Man Who Broke Into Auschwitz

The Man Who Broke Into Auschwitz